It Can’t Happen Here is a novel published by Sinclair Lewis in 1935. Lewis’s book is a satire depicting the rise of fascism in the United States. The populist demagogue Burzelius “Buzz” Windrip campaigns for the presidency on promises of economic reform and upholding traditional American values. He promises $5,000 per year to every citizen (this is a lot of money—over $100,000 in today’s dollars), to stop all immigration, to implement a complete ban on foreigners from taking American jobs, and to revoke citizenship for anyone with a “non-American ideology”. He also promises massive tax cuts for the middle class.

Against the backdrop of the Great Depression, mass unemployment, and general anger and hatred for politicians, Windrip, rather predictably, wins. He then establishes a fascist regime, with the help of a paramilitary force called the Minute Men who ruthlessly suppress dissent. He dismantles Congress, rips up the constitution, and creates a network of labour and prison camps.

Rather predictably, all this ends in disaster: Windrip is deposed and replaced by his campaign manager, Lee Sarason, who was the real architect of the regime. Sarason is then, in his turn, deposed by Colonel Dewey Haik, who takes the regime in a more militaristic direction, dropping the populist promises, and starting a war with Mexico. The book ends at this point, but whatever happens next isn’t going to be much fun.

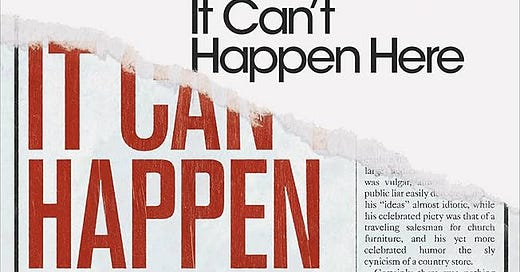

I can’t say that It Can’t Happen Here is a great book. The characters are mouthpieces for ideas, their relationships don’t entirely convince, and the plot isn’t always believable. It is written in a breathless, cramped style, as if Lewis were only allowing himself to breathe at the end of each paragraph. But it is undeniably compelling. I’m not the only person who thinks so. The cover of my copy has a quote from The Guardian describing it as “eerily prescient”. This is taken from an article, written just before the 2016 US presidential election, where It Can’t Happen Here is described as “the 1935 novel that predicted the rise of Donald Trump”.

But does this make any sense? There are some superficial similarities between Trump and Windrip. They are consummate populists who play fast and loose with the facts, as well as with their campaign promises. But to say that It Can’t Happen Here has much of anything to do with Donald Trump or his government makes little sense. To describe a book written in 1935 as predicting the rise of Trump is bizarre: Trump wasn’t even born in 1935.

Moreover, It Can’t Happen Here is set in a country that bears little resemblance to the America of 2016 (or 2025): WW2 hasn’t happened yet, the Great Depression is still ongoing (this is a large part of the reason why Windrip wins), fascism and Nazism are in the ascendant worldwide (this is another part of the reason). Windrip runs on the Democrat ticket, not the Republican—this is a world where a populist Democrat is more believable than a populist Republican. Finally, if It Can’t Happen Here was a prediction, it wasn’t a very good one: America did not become a fascist regime in the 30s or 40s, and even if you think Trump shows some fascist tendencies, he hasn’t followed the Windrop blueprint terribly closely.

What I found compelling about It Can’t Happen Here is not its predictive power but the way in which it assembles many of the elements you would actually have needed for America to follow Italy and Germany in their descents into a form of totalitarianism. Once you have read it, you are in a better position to assess the claim that America is on the verge of becoming a fascist dictatorship. I don’t think this claim is particularly plausible. Reading It Can’t Happen Here helps us see why it isn’t plausible: many of the necessary elements just aren’t there.

How Does it Happen?

Lewis tells the story of Windrip’s path to power in two ways: at a distance, from the perspective of the inhabitants of a small town in Vermont, and via some brief scenes involving the key players (Windrip, Sarason, and assorted politicians and media figures in his orbit). From this we can cobble together the basic outlines.

First, the background conditions are provided by the Great Depression at home and the rise of fascism and Nazism abroad. The Great Depression provides the main background for Windrop’s rise: it created a receptive audience for his promise of $5,000 annually to every citizen, which is a centrepiece of his campaign. This promise contrasts with his main competitors, Walt Trowbridge, the fictitious Republican candidate for President who eschews empty promises that will gain him applause, and Franklin Roosevelt, who runs as an Independent after losing the Democratic primary to Windrip. But Windrip’s platform—and Lewis’s book—borrows liberally from both Mussolini’s Fascists and the Nazis, both in terms of aesthetics (the mass rallies, the military imagery) and political structures (the Minute Men are clearly modelled on Mussolini’s Blackshirts).

Second, Windrip provides the necessary charisma and personality to get people to vote for all this. He is an electrifying speaker, with the power to move an audience and mobilise the masses. More than that, though, he is an American fascist: he speaks a language that Americans can understand. He isn’t Hitler, he isn’t Mussolini, he is a homegrown product of his country, with a good line in folksy rhetoric, and an evident distrust of politics and “ideology”.

Third, the Minute Men are the enforcement arm of Windrip’s regime. These uniformed thugs wear distinctive white shirts with blue bandanas, conduct public beatings of dissenters, destroy opposition newspapers, and use systematic violence to crush resistance. They also cheat, extort, and find various ways to enrich themselves at the expense of everyone else. Like their European counterparts, they are initially voluntary but are later formalised as a state-sanctioned military force with special legal protections.

Fourth, after the election, Windrip’s regime divides the country into new administrative districts that replace the states. These districts are ruled by “Corps Commanders” who have near-absolute authority and allow the regime to bypass local government and other traditional democratic institutions. The model here, both for Windrip and Lewis, seems to be Nazi Germany and the “Gauleiter” system. The economy is reorganised into a corporate state with businesses serving the needs of government. The model here seems to be Italian fascism, where capitalists sacrificed their autonomy but held on to their property and money—so long as they were willing to serve the state.

Finally, the regime creates a network of prison and forced labour camps. They also erect a comprehensive surveillance state, with citizens encouraged to report “anti-American” activities, and completely control the media, with independent newspapers either shut down or becoming effective mouthpieces for the regime. The model here could be any totalitarian regime of the time—Soviet Russia as well as Nazi Germany.

Is This Happening Now?

In It Can’ t Happen Here it isn’t entirely clear how all of this happens, or how it happens as quickly as it does. The rise of fascism in Lewis’s America is a good deal faster than the rise of Nazism in Germany or fascism in Italy; it happens in about a week. But Lewis’s story does contain what you might view as some necessary ingredients for fascism in America:

Mass social unrest and poverty (in the book, caused by the Great Depression and the aftermath of WW1).

A magnetic leader around which a cult of personality can be built.

Complete destruction of the existing legal system and democratic institutions, followed by the construction of a new system, entirely controlled by the regime.

Reorganisation of the economy into a corporate state with business subservient to government.

Complete state control of the press.

Construction of a system of labour and prison camps, nominally to house political prisoners, but with no judicial oversight.

A mass armed militia to enforce all of the above.

In America in 2025, most of these necessary ingredients are lacking. There is simply not social unrest or poverty on the scale of the Great Depression. Trump is not currently erecting a completely new system of governance, and complete state control of the press seems far off. While he is certainly mixing business with government, one often gets the impression that it is government that is subservient to business, not the other way round. Finally, there is not a mass armed militia numbering in the hundreds of thousands roaming the street to enforce compliance with the Trump regime.

In a recent article in Jacobin the historian (and host of the American Prestige podcast) Daniel Bessner argues that, while Trump’s second administration has taken an increasingly authoritarian turn, to describe it as “fascist” would be to misunderstand what is going on. America today is very different from the social and political contexts which produced Nazism and italian fascism. Interwar Europe was a period of mass social dislocation and hyperinflation. You had combat-experienced veterans roaming the streets and communism threatening to overthrow capitalism. The social conditions were ripe for fascism. None of this is the case in America in 2025.

For Bessner, Trumpism is not a foreign import. We can best understand it as an intensification of longstanding American antidemocratic traditons, rather than a rerun of Nazi Germany, or fascist Italy. Bessner highlights that Trump’s recent actions—especially the deportations of “criminals” for unspecified or fabricated crimes—build on established precedents: the long history of presidential overreach, the “theory of the unitary executive” developed under George W. Bush, and the sordid American history of arrests and deportations for crimes real and imagined. (This is not ancient history; remember what happened after 9/11). These things should trouble us, but they should trouble us because they reveal what America is and what it has been, not because they suggest that it is about to turn into Nazi Germany.

Does This Mean Everything is Ok?

No it doesn’t. Bessner’s piece is titled “This is America”. He thinks it is a mistake to draw glib comparisons between Trump’s America and Nazi Germany or Mussolini’s Italy because these comparisons provide false comfort. They foster the illusion that Trump and Trumpism is an aberration, that it is unAmerican. Bessner’s point is that it is very American—it is some of the worst tendencies from American history magnified, made explicit, brought to the surface. To refuse to acknowledge this is to refuse to understand what is happening.

In It Can’t Happen Here there is something of a tension. On the one hand, Windrip is presented as a very American fascist, as the culmination of historical tendencies that have had many different manifestations throughout American history—the Ku Klux Klan, the “Know-Nothing” movement of the 1850s, which violently opposed Catholic and Irish immigration, the Palmer Raids of 1919-1920, when the federal government arrested and deported thousands of suspected leftist radicals and anarchists. On the other, Lewis’s template for a fascist revolution borrows liberally from what was happening overseas. So which is it: homegrown American fascism or a foreign import?

Writing in the 1930s, Lewis could be forgiven for blending these influences. He was writing when fascism was ascendent globally, when America was not the all-dominant cultural and political behemoth it is today. It was perhaps plausible that, were fascism to arrive in America, it would simply be an American variant of what was happening in Germany and Italy. But Lewis clearly understood that fascism could emerge from America’s own political traditions, if the conditions were ripe, and the right person came along to exploit those conditions. Even if Trump isn’t that person, this is as true in 2025 as it was in 1935. Anyone who wants to stop this happening needs to wrestle with that fact, and this means avoiding facile comparisons with the Nazis.