As this is my first post, I better say a few things about what this Substack will be about. I’m a philosopher, with quite wide ranging interests: politics, psychology, literature, the usual things. At least at first, my posts will probably be about what is nowadays called “political epistemology”—knowledge and politics. More specifically, I’m interested in how we think about politics, the rationality (or lack thereof) of our political attitudes, the role of experts in the “knowledge economy”, things like that. I’m also interested in the disconnect between the nice, clean picture of how knowledge is produced that you get in contemorary philosophy and the messier reality as depicted in sociology of knowledge. I’m generally quite sceptical, verging into cynicism, hence the title of this Substack.

This post is the first of what will become a regular series, where I write about books I have read. For the past couple of weeks I’ve been wrestling with Jeffrey Friedman's 2019 Power Without Knowledge: A Critique of Technocracy. His diagnosis of technocracy's epistemic failings is insightful, and I thoroughly agree with the main line of critique (as I said: I’m prone to scepticism). But, as the book unfolds, Friedman stretches his scepticism beyond what his arguments can sustain. He also suggests an alternative to technocracy—what he calls "exitocracy"—that, to my mind, turns out to be no alternative at all. I thought I'd write up my complaints, on the off chance that it might be interesting to someone. I'll start with a summary for those who aren't familiar with Friedman's book.

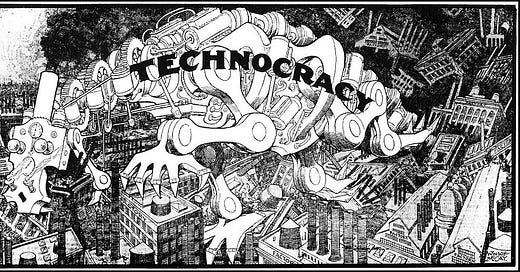

The Problem with Technocracy

Friedman works with a very expansive conception of technocracy as

"[a] polity that aims to solve, mitigate, or prevent social and economic problems among its people" (p. 5).

This means that, for Friedman, technocracy encompasses both "epistocracy" (a polity where elites—academics, policy experts, civil servants—are "in charge") and what he calls "citizen technocracy" (a polity where citizens are "in charge" but they try to solve social problems). The idea is that, for all the differences between epistocracy and more populist forms of citizen technocracy, they are both based on the idea that someone has the requisite competence (and motivations) to remedy social problems. The epistocrat and the populist differ on who has the competence (elites vs. "the people").

The heart of Friedman's critique of technocracy is simple:

"modern social problems are likely to be complex enough to pose serious epistemic challenges to technocracy" (p. 35).

Friedman does not just mean that we shouldn't entrust elite epistocrats with solving social problems. He means that social problems are typically so complex as to defy attempts to solve them.

Friedman thinks social problems defy our attempts to solve them because of what he calls "ideational heterogeneity"—the divergent and unpredictable ways humans interpret their circumstances and respond to policies. As he puts it

"Human actions are driven by human ideas, and human ideas are, as a practical matter, unpredictable" (p. 126).

Because we can't predict how humans will view the social problems the technocrat is trying to solve, or how they will respond to attempts to solve them, technocratic policy making is inherently risky and unpredictable.

Why don't technocrats recognize this fact? Friedman argues that both epistocrats and citizen-technocrats suffer from "naïve technocratic realism"—the assumption that the nature of social problems is easy enough to grasp, and so failure to grasp them is indicative of some psychological flaw or ideology.

Take, for example, the debate about rent controls. Proponents of rent controls typically view opponents as indifferent, if not downright hostile, to the plight of renters; opponents typically view proponents as ignorant of economic realities and caught up in juvenile anti-capitalist sentiments. Neither side acknowledges that the empirical evidence admits of different interpretations, such that, even if you come down on one side or the other, it is implausible to hold that the "truth" here is self-evident, such that the only reason someone could fail to grasp it is psychological or ideological. This pattern appears across countless policy debates, with each side viewing their own solution as self-evident while attributing disagreement to others' cognitive or moral failings, rather than the sheer complexity of the issue at hand.

Against this naïve realism, Friedman adopts a sceptical, agnostic stance on which many of our beliefs about social problems and complex social systems may be false. The hitch, though, is that we cannot reliably identify which beliefs are false. We do not know what we do not know. Worse, he sees no realistic prospect of substantially improving our position.

Friedman's argument is extremely ambitious: the opacity of social problems and systems is not a mere temporary limitation that might be overcome with better science or improved statistical methods. It is inherent in the very nature of human social arrangements. He argues that judicious technocratic governance would require:

Knowledge of which social problems truly matter

Knowledge of their root causes

Knowledge of which interventions would solve them

Knowledge of all costs, including unintended consequences

He then proceeds to show why each type of knowledge is extremely hard to obtain. You can't simply rely on personal experience, as it may be unrepresentative. You also can't simply rely on data, as data without theory is meaningless (you need a theory to tell you which correlations in your data might be meaningful). Even when you have theories backed up by some data, you face the problem that whatever data you have will never come close to establishing one theory over a host of alternatives.

Most importantly, when you put any social theory into action, you face the problem of unintended consequences. Mistakes at the level of which social problems truly matter lead to important problems remaining unaddressed, mistakes at the level of causes or interventions lead to policies that don't work, and all policies face the problem that they might ultimately do more harm than good. This, of course, is the problem that many raise for rent controls, proponents of which think will make housing more affordable, and opponents of which say will have the opposite effect.

Friedman wants to generalize this insight, but he also wants to turn it against the sorts of policy proposals typically favoured by the economists who are against rent controls. Any policy may turn out to have significant unintended consequences, and Friedman thinks that this is grounds for deep scepticism about any form of technocratic governance, even if it takes economics as its guiding star. Everyone, whatever their political views, should be sceptical about any attempt to engineer social outcomes via policy making.

The Media: Beyond Innocent Misinterpretation

Friedman is as sceptical about the prospects of ordinary citizens solving social problems as he is of elite epistocrats solving them. But how does Friedman think ordinary citizens form an understanding of social problems in the first place?

Friedman draws on Walter Lippmann's work on public opinion. Simplifying, Lippmann highlighted two central facts. First, interpreting the world is inevitably difficult. We achieve this task via stereotypes or interpretive frames that we use to filter and make sense of the enormous mass of information with which we are confronted. These interpretive frames are liable to distort, but there is no alternative to using them. Second, it is a mistake to think that there is an institution—journalism—that can make this task easier because journalists are presented with the exact same problem as everyone else (making sense of a complex world) and they use the same tools to tackle it (interpretive frames that inevitably distort).

The upshot is that Lippmann rejected explanations of media bias that emphasize deliberate manipulation by powerful interests. Instead, he attributed misleading media coverage to the inevitable difficulties that journalists face in interpreting the world. For example, in discussing then-contemporary coverage of the Russian revolution in the media, Lippmann attributes mistakes in the coverage to the sheer difficulty of accurately reporting of events in Russia, not a deliberate will on the part of journalists to deceive their audience.

I find Lippmann's analysis compelling. But there is a problem here. Friedman, following Lippmann, may well be right that any attempt to accurately report a complex event like the Russian revolution is going to get things wrong, perhaps badly so. But that doesn't adequately explain something you might think needs explaining, which is why journalists tend to err in particular directions. Why, to use Lippmann's example, did journalists writing about the Russian revolution in the early 20th century paint one picture rather than another? Why, to use a more contemporary example, do media outlets tend to frame industrial disputes in terms of disruption and inconvenience to the public rather than in terms of legitimate responses to deteriorating pay and working conditions?

These interpretative patterns are not random. If they are mistakes—and Friedman himself seems to think they often will be—they clearly reflect institutional biases and a tendency to favor some perspectives over others. These biases need not manifest in journalists deliberately setting out to deceive their public by cynically presenting events in ways that serve their interests, or the interests of the proprietors of the media outlets that employ them. They may instead manifest in the fact that media outlets hire journalists who have interpretive frames which lead them to present complex events in certain ways—ways which fit with how the proprietors of these outlets would themselves represent them.

This is relevant to another point from Lippmann with which Friedman seems to agree. He quotes Lippmann:

"There is no magic in ownership that enables a business man to know what laws will make him prosper" (p. 107).

The point that a business man (or woman) may be wrong about what is in their interests is well-taken, and it speaks against those who want to depict a world of evil omniscient capitalists relentlessly pursuing their own interests at the expense of others. But this insight in no way negates the force of concerns about concentrations of power, especially in media ownership. The core problem is not that media barons are omniscient deities with the power to manipulate the public. It is that they have the power to dictate which version of the facts the public will encounter. This is a problem so long as you think—as Friedman clearly does—that the chances the media barons have a monopoly on the truth are extremely low.

Ideational Explanations: Toward Explanatory Pluralism

I have some other disagreements with Friedman. One concerns what he calls "epistemological individualism", which is a doctrine that privileges ideational explanations of human behavior over material and structural factors (that is: explanations in terms of what people think rather than in terms of incentives or material interests).

Friedman makes some points in defence of epistemological individualism which are clearly correct: people interpret their circumstances in diverse ways, and we should not mistake our (the theorist's) interpretation of someone's circumstances with their (the actor's) interpretation of their own circumstances. He is also correct in thinking that this is one of the major failings of certain social sciences: it is a mistake to infer, from the fact that someone who was aware that they were under incentive X would do Y, that they will in fact do Y. They may not be aware that they are under incentive X, think they are under incentive Z, or something else, and all of this makes a difference to what they will do.

However, Friedman goes further than this. He says:

"We should explain human behavior in terms of the ideas in the 'heads' of individuals, rather than in more collectivist ways, or in ways that bypass ideas/interpretations entirely" (p. 140).

It is not just that ignoring subjective interpretations will lead to mistakes when we try to predict what people will do or explain why they did what they did. We should foreground subjective interpretations, and ignore other factors, such as group membership, or the material factors which some might think provide the basis for these subjective interpretations.

The 2016 Brexit referendum in the UK nicely illustrates the problem with this approach. Imagine that, before the vote, you set yourself the task of predicting how people will vote. Or imagine that, afterwards, you set about trying to explain why people voted as they did. There is value in an approach which looks at how particular demographic groups voted or were likely to vote (young people were typically against; older people typically for) and then uses someone's membership in a particular demographic group as the basis for a prediction or explanation. Of course, any prediction made on this basis might be wrong: some young people voted for Brexit and some older people voted against. But the same goes for any attempt to predict or explain based on a presumed understanding of the ideas in someone's head.

To extend this Brexit example further: While demographic data could tell us broad voting patterns, it couldn't explain why a particular older person might vote against Brexit, or why a young person might support it. Similarly, while understanding individual interpretations might help explain specific cases, it wouldn't capture the broader social patterns that emerged. What's needed is an approach that can accommodate both types of explanation.

A better option would be to take a pluralistic approach to prediction and explanation. For some purposes, and in some contexts, you might want a style of explanation that foregrounds subjective interpretations and the ideas in people's heads. But for other purposes and in other contexts you might want to take a different sort of approach. An adequate explanatory framework needs to incorporate ideational, collectivist and materialist elements, and perhaps other elements besides. We can, with Friedman, reject simplistic views on which material circumstances determine behavior while still recognizing that ideas come from somewhere, and are in part shaped by material circumstances and institutional environments.

Social Science: The Baby and the Bathwater

Another disagreement concerns the severity of Friedman's critique of what we might term "predictive" social science. He condemns the social sciences—in particular economics—for exhibiting what he calls a "pathological pressure to predict":

"Neoclassical economics relentlessly disregards the very possibility of ideational heterogeneity—a habit that perfectly suits the practice of behavioral prediction, although not reliable prediction... A policy science that, like neoclassical economics, ignores ideational heterogeneity may be able to issue a steady stream of behavioral predictions, but these predictions cannot be judicious in the requisite sense" (p. 181).

Why does Friedman single out neoclassical economics? Because it is built upon the insight that "incentives matter", but it is blind to the fact that incentives do not by themselves do anything. What makes us act are not the objective incentives we are under but our perceptions of the situations in which we find ourselves. An economist might say that an employer, faced with a rise in the minimum wage, has an incentive to fire some staff to keep wage costs manageable. But the employer might not see things this way: they might simply fail to grasp this logic, or they might decide to invest more in staff as a way of gaining an advantage over their competitors, who they assume will be trying to reduce staff costs.

These points are, again, insightful. But they get caught up in some sweeping judgements that seem to go from the fact that technocrats are prone to overconfident and simplistic analyses of complex situations to the conclusion that making reliable predictions of how humans will behave is practically impossible. We can reject technocracy as Friedman understands it without rejecting the possibility of predicting human behavior. We can reject the hubris of technocratic certainty while still finding value in careful and qualified predictions of the sort that the social scientist is—or should be—interested in.

Take public health interventions like the UK's sugar tax on soft drinks, which was introduced in 2018. This has led to measurable reductions in sugar consumption, with manufacturers reformulating products to avoid the tax, and consumers shifting their purchasing patterns accordingly. That this would be the result of implementing the tax was—I presume—not a surprise to anyone.

To be sure, someone who wants to argue, whether on the basis of these predictions or on the empirical confirmation of their accuracy, that the sugar tax would be a net positive for public health in the UK arguably faces all of Friedman's arguments: they haven't considered any of the possible unintended consequences of the tax.

What might these unintended consequences be? Perhaps manufacturers replaced sugar with artificial sweeteners that turn out to have negative health effects we don't yet fully understand. Perhaps the higher cost of sugary drinks led some consumers to substitute other unhealthy but untaxed products. Perhaps the political capital spent on implementing the sugar tax could have been spent on more effective public health measures. These are all possibilities that a technocrat implementing the sugar tax might have failed to consider.

But none of this in any way invalidates the basic point that the immediate effect of the tax was predictable, despite the ideational heterogeneity of the UK public. We can agree with Friedman about the shortcomings of technocracy as a form of governance without throwing away the predictive social sciences which are supposed to provide the basis for that form of governance.

The Spiral of Conviction: A Self-Defeating Critique

The next disagreement concerns what Friedman calls "the spiral of conviction". He argues that social science—at least the branches of it that serve technocracy—systematically selects for closed-mindedness and dogmatism. This is because any would-be epistocrat is under two pressures: first, a pressure to make concrete behavioral predictions, which requires closed-mindedness, and second, a pressure to express a high degree of confidence in those predictions, which requires dogmatism. This means that technocracy produces (because it requires) a cadre of closed-minded and dogmatic epistocrats.

How does this work, exactly? Imagine, for example, a would-be epistocrat who might be of service to a government planning to introduce a sugar tax. They would only be useful if they were willing to make a concrete prediction about the (positive) benefits of implementing the tax, which requires ignoring all the possible scenarios in which the tax has unwanted unintended consequences. They would only be taken seriously if they expressed a high degree of confidence in their prediction (who would implement the tax otherwise), which requires at least the surface appearance of dogmatism.

Friedman's analysis is, again, insightful. I do however have some doubts about how well it fits with the general argument of his book. Friedman, recall, is keen to stress the extent of ideational heterogeneity: people perceive the world in a diverse range of ways, and, from the fact that you, as a theorist, perceive their situation in a certain way it does not follow that they perceive their own situation in that way.

We can apply this to our would-be epistocrat. Friedman may be right that they are operating under a system that—objectively speaking—incentivizes closed-mindedness and dogmatism. But that doesn't mean that our would-be epistocrat perceives things this way. They might adopt the closed-minded, dogmatic posture Friedman describes, but they might also attempt to differentiate themselves from other epistocrats precisely by emphasizing uncertainty and refusing to be dogmatic. More generally, why does Friedman assume that would-be epistocrats will understand the "logic" of technocracy in the way that he does? He may be correct in assuming this—I suspect he is in fact correct, with the proviso that there will always be exceptions—but he seems to be in a peculiarly bad position to justifiably assume it, given his own theoretical commitments.

In other words, Friedman's critique of the "spiral of conviction" seems to contradict his own emphasis on ideational heterogeneity. If people interpret their circumstances in unpredictable ways, then surely some epistocrats will interpret their role in ways that resist the pressures toward closed-mindedness and dogmatism. By assuming that all epistocrats will respond to incentives in the same way, Friedman seems to be committing the very error he criticizes others for making.

Exitocracy: An Alternative?

In the final chapter, Friedman proposes an alternative to technocracy that he calls "exitocracy". An exitocracy is a system focused on enabling individuals to escape rather than solve social problems. As he explains:

"An exitocratic government would unquestionably be a state. But it would differ from a technocratic state in that, instead of attempting, case by case, to produce solutions to any and all social problems that might arise, its cardinal goal would be to provide a framework within which individuals could attempt to solve—or, better, escape—the problems that afflict them as individuals" (p. 322).

Citizens can know when a service is unsatisfactory and can recognize when an alternative works better, even if they can't identify why the original service failed or how to fix it. For example, Friedman discusses customers in Nigeria switching from rail to bus services due to dissatisfaction with the railways. Customers could recognize that the rail service was inadequate, and that the buses were a better alternative, simply due to their own experiences, and without having to understand why the rail service was inadequate, or the bus service better. This sort of direct, simple experiential knowledge facilitates effective problem-solving without any technocratic expertise whatsoever.

Exitocratic governments differ from technocratic in that they provide their citizens with opportunities to exit from inadequate systems rather than attempting to improve those systems. More generally, in shifting from technocracy to exitocracy we essentially give up on the idea that the state can solve social problems.

Friedman recognizes that left-wing readers are liable to baulk at this. But it is unclear what he wants to say about it. On the one hand, he recognizes that, for "true" exitocracy, everyone would need the ability to exit (to leave a bad job, to stop using a malfunctioning social service). As it turns out, his understanding of what it would mean to have the ability to exit is exactly the sort of thing a traditional socialist would say: it requires redistribution on a grand scale—redistribution of the sort we have never seen in any extant social democracy.

On the other hand, Friedman thinks that, absent massive redistribution of resources, capitalism is our best means of facilitating exit from malfunctioning systems:

"The epistemic advantage of economic competition is not that any identifiable capitalist is less fallible than any other, or that capitalists, as a group, are less fallible than technocrats, as a group, but that capitalism allows more than one fallible solution to be tried concurrently, with those affected by the problem using personal experience to judge which of the competing solutions is relatively acceptable" (pp. 328-9).

While capitalists no more know how to solve social problems than technocrats, capitalist competition produces a range of different exit opportunities. These exit opportunities may be far from ideal—they may amount to the opportunity to work in a sweatshop rather than earning money by selling rubbish—but they are still exit opportunities, and Friedman's defense of exitocracy over technocracy is based on the claim that whatever exit opportunities are provided by capitalism are preferable to the false promises of technocracy.

What are we to make of all this? I must admit to being puzzled. Friedman's "ideal" version of exitocracy, on which we have a massive redistribution of wealth that provides equal opportunity of exit, is as idealistic as traditional forms of socialism. Worse, any attempt to realize it would seem to face all the problems that Friedman raises for technocracy. Whatever set of policies would be required to achieve redistribution would, clearly, be liable to lead to all sorts of unintended consequences. Why would we be in any more in a position to know what those consequences would be than we are in a position to know what the consequences of the policies proposed by technocrats would be?

Friedman does address this sort of worry: in practice, exitocracy will always require a bit of technocracy because there will always be a role for the state in ensuring the availability of some exit opportunities. But his response to it is unsatisfying:

"While technocratic reasoning will have to be deployed in providing exitocratic public goods—this is what makes exitocracy a form of technocracy, even if an 'extraordinary' one—the inevitable errors that result will be offset, to some (putatively significant) extent, by the fact that these public goods will enable people to solve social problems in the private sphere" (p. 341).

This seems to amount to the hope that whatever technocrats need to do to preserve exitocracy will not be subject to the worries about unintended consequences that plague technocracy. Even if this were the case, it is hard to see how the exitocrat could be in a position to know that it is the case.

Final Reflections

These criticisms might give a misleading impression of the extent to which I disagree with Friedman. There are several areas where I completely agree with him. First, though I have some quibbles with the uses to which he puts it, Friedman's epistemological individualism and his emphasis on ideational heterogeneity captures the importance of a kind of explanatory symmetry: we should not explain beliefs we view as false via psychological or ideological mechanisms while treating beliefs we view as true as simple reflections of reality. (Where I depart from Friedman is in thinking that—at least some of the time and for some purposes—it is useful to explain both beliefs we view as false and beliefs we view as true via psychological or ideological mechanism. Back to the Strong Programme!).

Second, while I think Friedman is too quick to dismiss vast swathes of social science, he is entirely correct in thinking that, whatever the merits of social science, it cannot do what the epistocrat asks of it. Importantly, Friedman avoids the mistake of pinning the blame on the inadequacy of social science as it is currently practiced. It may well be that certain social sciences deserve criticism for a lack of methodological rigor, and it may well be the case that the political leanings of social scientists distort the field. But the fundamental problem is that social reality is enormously complicated. Studying humans and human beings is not like studying atoms because human behavior is a function of how humans perceive the world, not the world as it objectively is.

Third, while Friedman sometimes takes his scepticism too far, he is right to be worried about the difficulties of obtaining technocratic knowledge. He is also right to be worried about the mindset which technocracy tends to create. While Friedman doesn't put it this way, the technocrat is someone who is susceptible to the so-called Politician's fallacy: we need to do something about this pressing social problem, this policy is something, so we should pursue this policy. The fact that the technocrat can often dress this up in fancy language—cite some statistics, throw in some social theory—does not circumvent the fallacy. Not all problems have remedies, and many problems are so complicated that our chances of remedying them are slim.

Ultimately, I'm persuaded by Friedman's case against technocracy, but not by his exitocratic alternative to it, or by his attempt to pin the problems with technocracy entirely on social science. This leaves us—or at least me—in a tricky position. If not technocracy or exitocracy, then what? Perhaps the lesson of Power without Knowledge is that it is incredibly difficult to justify a political system on the grounds that it is liable to lead to good outcomes. If it is hard to know what the consequences of implementing a policy like a sugar tax would be, it is a good deal harder to know what the consequences of shifting from one political system to another would be, or what we might be missing out on by not shifting from our current system to a different one.

If this is right, then Friedman might—perhaps contrary to his intentions—have demonstrated the irrelevance of epistemology to politics. The difficulty of reliably predicting the consequences of our political choices may force us to abandon consequentialist justifications for political systems altogether. Instead, we might need to focus on the intrinsic merits of different political arrangements: their fairness, their respect for individual rights, their democratic nature. These considerations may prove more enduring than any speculative predictions about which system will produce the best outcomes in an unpredictable future.

Fascinating stuff!

One quick thought on incentives and social science. The idea that people only respond to incentives in familiar textbook ways (eg, buying less of something when the price increases) when they recognize the incentives as such strikes me as a mistake.

There's a fruitful tradition in economics of evolutionary game theory, where the basic insight is that economic actors do *not* have to decide what to do by reference to concepts from economics in order for those concepts to play a role in predicting and explaining market outcomes.

If firms that make profits tend to grow, and firms that experience losses tend to shrink and go out of business, then even if managers are making decisions randomly, without anything like a conscious attempt to maximize profits, you should expect that over time the firms that remain in the market will be pursuing (roughly) game theoretically optimal strategies. This is analogous to the idea that animals will tend to behave in "rational" ways (eg, not leaving calories or mating opportunities on the table) even though they're usually not consciously optimizing; conspecifics in earlier generations who pursued less effective strategies failed to reproduce.

Thank you for this very interesting summary and partial critique of Friedman's work. But I find it puzzling that Friedman (and McKenna) discuss these issues without referring to the unmissable work by Philip Tetlock and his collaborators on expert forecasters. (Which generally think in a totally different way from the overconfident 'experts' who serve as talking heads in the media) These expert forecasters are foxes rather than hedgehogs, sound something like Bayesian reasoners, constantly updating their predictions, and make probabilistic predictions. Laypeople who think this way can predict geopolitical events better than CIA analysts with access to classified information not available to the laypeople. But the predictions of even the best forecasters are not spectacularly better than chance - though they would do well in constantly repeated bets. And (if I remember correctly), if they have to predict events further in the future, at about six months even the best forecasters cease doing any better than chance. The other thing I miss in Friedman's account is the possibility of doing smaller scale experiments before introducing new policies, and in general the Popperian notion of piecemeal engineering - doing policy changes in small increments and seeing what happens after one smallish step before setting the next smallish step. I've just started reading Nate Silver's The Village and the River, and the River mindset (silicon Valley, poker players) may be related to that of Tetlock's Superforecasters. Successful venture capitalists must be able to predict the future well enough to have their hits outweigh their misses. The reason for their success is not that they are good at avoiding misses. I don't know whether rethinking in probabilistic terms all the issues Friedman discusses could lead to a less dire view than the one Friedman presents. But meanwhile kudos to him and McKenna for developing the view that we normally utterly overestimate what technocracy can achieve.